AWS Lambda is the archetype of a class of cloud computing products called serverless functions-as-a-service, or FaaS.

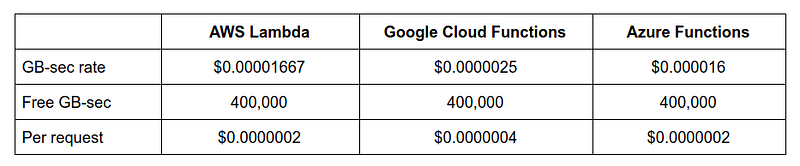

Others in this product class include Google Cloud Functions and Azure Functions, both of which share the same billing model as Lambda, but with different rates and service limits.

This post looks at the serverless FaaS billing model in general, but focuses on AWS Lambda’s current pricing (as of September 2017). Its goal is to point out some observations that may help in reducing or preventing unexpectedly large AWS Lambda bills. Many of these may also be relevant to other products that share a similar billing model.

Lambda Functions

A Lambda function is a piece of application software that runs in a short-lived container to service a single request or event. Although the use of the term “function” can suggest that the code must consist of a single function, Lambda functions are regular processes that can also, for example, spawn child processes. They must conform to a specified interface, but can otherwise contain arbitrary code.

Each Lambda function can be “sized” by setting the maximum memory size (GB) parameter in the Lambda Console or using the API. This value also affects the CPU shares allocated to the function when it runs, but in a manner that is not currently disclosed by AWS. Lambda also allows limiting the maximum function execution time (seconds) for a function, to prevent runaway or hanging functions from driving up cost.

Since Lambda functions run only when a request must be serviced, they only incur charges when used. The general pricing model adopted by serverless FaaS providers is based on two numbers per function invocation:

- Maximum memory size (GB): note that this is not the actual memory used by the function, but rather the maximum memory size parameter in the Lambda function’s configuration. If you reduce your function’s memory usage, but do not adjust this configuration parameter accordingly, you will not see a cost reduction from the reduced memory usage.

- Function execution time (seconds): the actual amount of clock (wall) time that the function invocation took to run. Note that if a Lambda function makes an outgoing network call and sits idle waiting for the result, the time spent idle is still counted in the function’s execution time, i.e., this is not a measure of CPU usage.

For each function invocation, these two values are multiplied together to produce a number with the unit GB-sec. After allowing for a monthly allowance of free GB-sec from the free tier, the billable compute cost is the total GB-sec across all function invocations, multiplied by a fixed GB-sec rate. This fixed rate is currently the following for three popular FaaS services.

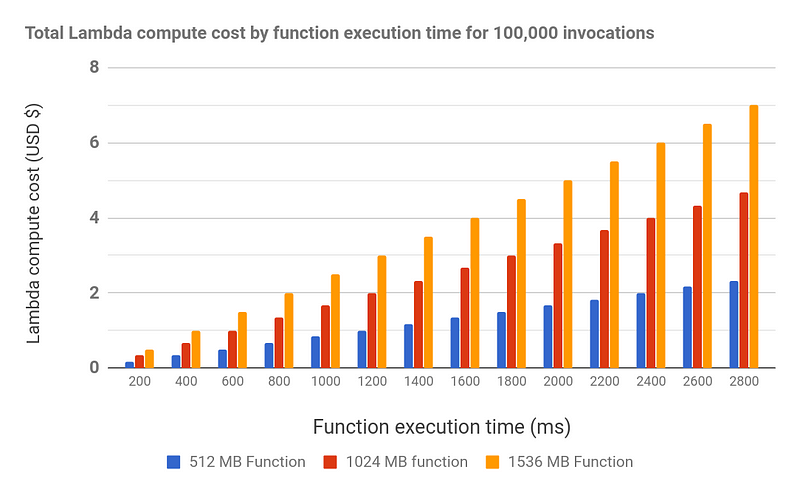

Since GB-sec is a composite unit, it can be unintuitive to reason about. Focusing on AWS Lambda’s current pricing, the following chart shows the cost of executing 100,000 invocations of a Lambda function that executes for a varying amount of time, broken down by three different maximum memory sizes. Note that each invocation may have to start a language runtime and load third-party libraries before getting to user code, all of which add to the function's billable runtime for each invocation.

It can be helpful to remember that a GB-sec represents neither a gigabyte nor a second, and is the first composite unit to be used for commercial cloud product pricing in recent memory.

Spreadsheet-inclined users may want to look at the data in this public, read-only Google Sheet.

Observations

-

Costs are multiplicative in function memory size and execution time. Suppose that a Lambda function uses 512 MB of memory and executes in slightly less than 200 milliseconds. After a code change, the function now needs 400 milliseconds to run (double), and 1024 MB of memory (double). The total compute cost increases 4 times. If the memory requirement is instead tripled to 1536 MB, the total cost increases 6 times. If both the memory requirement and execution time are tripled, the total cost increases 9 times (spreadsheet). The impact of multiplicative costs may not be intuitive in that small changes to either function memory size or execution time can cause large changes in the total billable cost.

-

Processing delays can be expensive. Suppose that a 512 MB Lambda function executes in slightly less than 200 milliseconds, with a hard limit of 5 seconds. As part of its processing, the function calls an external service over HTTPS and waits for a response before ending. Suppose that network congestion or an external service degradation adds a spike of 2 seconds to each network call. For the duration of the latency spike, the extra 2 seconds of Lambda running time will increase cost 11 times, from $0.17 per 100k requests to $1.83 (spreadsheet).

-

The free tier can run out quickly. Suppose that a service must support a sustained request rate of 100,000 requests per hour (sustained 27 requests per second). At this rate, the free tier of 400,000 GB-sec per month will run out in approximately 1 hour for the following function sizes (spreadsheet):

- 512 MB, executing for 8 seconds per invocation

- 1024 MB, executing for 4 seconds per invocation

- 1536 MB, executing for 2 seconds per invocation

-

Spot pricing may sometimes be cheaper than Lambda pricing. For some types of sustained workloads, using a reliable, distributed work queue in conjunction with preemptible, spot priced instances can allow fine tuning of the price/performance ratio, while still allowing a function-based, event-driven application architecture.

As a concrete example of the observation on spot pricing, consider the following numbers, drawn from the Baresoil Image Resizing Benchmark:

-

A fixed-sized cluster of 20 c4.2xlarge spot instances can resize at least 120,449 images per hour for a total cost of $1.82 per hour, using a median of 1 second of processing time per image (code and data). This can be taken as a lower bound on the performance of an EC2 spot fleet where work is distributed evenly across nodes.

-

The exact same code and workload on Lambda costs $2.28 to run using a 320 MB function memory size (the smallest possible for this task), which is 33% higher than the spot fleet. With the largest 1536 MB function size, the Lambda cost is 59% higher than the spot fleet (spreadsheet). Processing times ranged from 800 ms to 3700 ms depending on the Lambda function size, as reported by Lambda's "billable duration" metric (raw data).

On the other hand, if you are currently processing 120,449 images per hour using spot priced queue workers, you may be able to process the same actual workload in minutes rather than an hour for just a 33% increase in costs, using Lambda’s default concurrency limit of 1000.

Summary

-

Monitor and adjust maximum memory size and execution time parameters. Since the cost incurred by a Lambda function invocation is multiplicative in its execution time and memory size, increasing or reducing both by even a small amount can have an unexpectedly large impact on billable cost. Monitoring actual function execution time and memory usage allows these parameters to be set closer to their required value, which also limits the cost impact of runaway or hanging functions. Note that this does (and should) cut into the "no operations" myth surrounding serverless services.

-

Avoid high maximum execution time. A common engineering instinct is to build in a safety buffer beyond minimum requirements. If a Lambda function normally runs in 200ms, it may be tempting to set the maximum execution time parameter to something large, like 10 seconds. However, consider the additional cost incurred by Lambda functions that are waiting on flaky external services, versus having the function terminate earlier and return an error to its caller.

-

Consider EC2 spot pricing for queue-driven workloads. If traffic is predictable and sustained, an application architecture based around a reliable queue and spot priced queue worker instances may be cheaper than Lambda functions. This may change if Lambda starts supporting spot priced Lambda functions in the future, such as is the case with SpotInst.

-

Expect a price war soon. The serverless FaaS model is already heading towards a degree of organic standardization when it comes to features and interfaces, helped by frameworks like the Serverless Framework. Once serverless FaaS becomes a commodity cloud service, providers may only have room to compete on pricing. We can already see that Google has chosen different rates than Amazon and Microsoft, opting for a lower GB-sec rate but a higher per-request rate. In the future, some things we could conceivably expect are native spot (preemptible) pricing for serverless FaaS, and a lower slope to the cost curves shown in the earlier chart.